Sharp blades and muscles: These are the lab tools used lately by my class. We’ve been mapping and eradicating privet from Bluebell Island, a local hotspot for wildflowers. Privet is a non-native invader and it overshadows and kills native plants.

Setting up the mapping transect.

The View from Lazy Point used as a field clipboard. The class combines field work with discussions of readings, so hardback books find multiple uses. I hope Carl Safina would approve of the students’ improvised use of his fabulous book.

This project started in 2001 when my Ecology class measured and mapped every privet stem on the east side of the island where the flower populations are concentrated. I repeated the project in 2007 with my Seminar in Ecology and Biodiversity, then this year with the Advanced Ecology and Biodiversity class.

We uproot the privet plants. Easy to do when they are small…

…not so easy when they are big. Katie pulled this one by hand. All that work on the swim team has paid off. No need to pull out the saw.

We’re building an interesting dataset. There are not too many places where we have long-term data on the details of how invasive plants respond to attempts at control. Along with this scientific goal, we’re hoping to leave the island in much better shape for wildflowers.

What have we found? At first glance, the project seems to be failing spectacularly. There are many, many more privet plants within the project area now than there were in 2001.

Total number of privet stems increased over time.

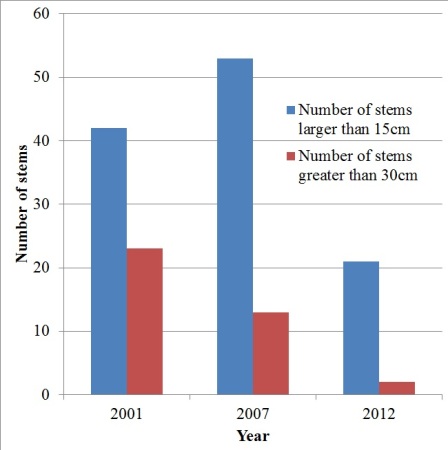

But this graph does not capture the whole story. The vast majority of the stems in 2012 are tiny little sprouts, reaching to knee-height. In 2001, the stems reached over our heads and were casting dense shade.

The number of large plants (>15 or 30 mm in diameter) has decreased over time.

The average (mean) size of stems decreased over time. The graph also shows that the variability in stem diameter (standard error of the mean) also decreased over time.

So we’ve lost big plants and gained lots of little seedlings. It seems that the removal of large privet plants allows light to reach the ground which encourages both wildflowers and new privet plants. Long term success will depend on continued visits to the island to stop new privet sprouts from getting too big. The rest of the island, outside the study area, serves as an interesting contrast. It is overrun with large privet plants and the wildflower populations are dying out. Eradication of privet over the whole island would be a more major undertaking than could be accomplished by one class, even with many days’ work. Fire and goats might help.

Tyler Johnson prepared this map of the location of every privet stem (2007 data) in Dr. Chris Van De Ven’s GIS class. We’ll be expanding the mapping analysis in coming months to include all three sampling periods, examining whether the spatial distribution of privet has shifted over time.

Bluebell Island is owned by the South Cumberland Regional Land Trust and was bought with contributions from naturalists in Sewanee and beyond. It hosts dense populations of bluebells, trout lilies (including white trout lily), and even the rare dwarf trillium. I’m grateful to the SCRLT board for their continued support for this work, a project that started when I served on the board but has now extended for more years than I at first imagined.

Privet is not the only threat to the island’s famous wildflower display. Gill-over-the-ground is another non-native plant species that has made inroads on the island, as has exotic honeysuckle. In addition, poachers have dug significant numbers of plants over the years. About ten years ago they hit the island so hard that many parts looked as if they had been rototilled. The bluebells gradually regrew. This year, the trespassers hit again, digging large patches. I’m pretty sure that one of these patches encompasses the only known plant of the dwarf trillium in this part of Tennessee, so this rare species may now be extirpated from the island. The poachers are targeting bluebells, but the tiny trillium plant got taken as collateral damage. I may be wrong – we’ll know in the spring – but the digging crosses the exact spot where the plant lives. So if you’re tempted by the pretty bluebells for sale at the nursery, I’d advise you to skip them unless the seller can prove to you that they were nursery-propagated.

Despite the pressures, Bluebell Island is still a marvelous place. In addition to the flowers, old trees provide great habitat for woodpeckers, owls, and wood ducks. Beavers and mink swim the river. Migrant birds ply the riverbanks in the spring. Butterflies are abundant in summer. The river itself is different on every visit. It runs clear and calm in winter dry spells; swells silty and trashy in the floods; then courses bluegreen in the warm algal summer months. Suwannee is a river, but Sewanee is not; so I enjoy my visits off “the mountain” to see some real flow.

Beavers came around after us and snacked on the discarded privet stems.

I’m grateful to the many cohorts of Sewanee students who have yanked, sawed, tweaked, measured, mapped, and analyzed these thousands of privet stems.

Sewanee’s Bio 315 class in “gaze at the sun as if something inspiring and important were happening” pose after pulling 4275 privet stems. The largest vanquished stem is held as a trophy. We omitted the blooding ceremony.

It was really neat reading this post knowing that I was in that 2007 class! Glad to see that a slow but sure difference is being made on Bluebell Island :-)

Marie, You were not only in the class, but went the extra mile (several, actually) to come back and finish up the last patches after class was wrapped up. So: a BIG thank you!!

Hope all is well with you.

I remember our field trip there for an ornithology class, such a beautiful spot. Glad to see that you are taking care of it.

Hi Laura, Yes — I call that lab “riparian ornithology” but it is basically an excuse to go and check out what cool things are on the island. If we’re lucky, the first blue-gray gnatcatchers and black-throated green warblers are about. If not, then at least another generation of Sewanee students gets to see the flowers…

David: I often uproot invasive, non-native Asian bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus) in the woodlands in the northern Piedmont natural area for which I am responsible, but I wonder as I “unzip” the plants’ roots from the ground if I’m not just creating a soil disturbance upon which new bittersweet seedlings will capitalize. (I’ve thought about performing a formal study, but generally am too desk bound to get a project off [or on] the ground.) The same thing might be happening with the privet on Bluebell Island. Perhaps it might be more judicious to have the students cut the stems with loppers, and then paint herbicide on the cut ends of the privet to control the infestation.

Scott, Thanks for this comment. Interesting possibility. For the larger stems (which we have not seen lately), this is exactly what we did: cut and paint. The soils on Bluebell island are very sandy so the privet comes up easily. I suspect that we’re not creating much of a seed bed with this process. A bigger issue may be fragmentation of root systems from which new plants may sprout. Some of the ones we pulled this time definitely came from old roots. Others seem to be newly seeded.

The bittersweet around us is incredibly tenacious. I have some patches in my garden that I’ve pulled many many times over the years. It weakens, but then comes back. Tough species.

David, besides soil disturbance, it would be interesting to study the seed bank. Our problem is scots broom (Cytisus scoparius). Long lived seeds – and pulling brings up more. I try to pull the small ones only when it’s wet, and to use the Brady sisters (“Bringing Back the Bush”), low disturbance methods whenever possible, then cut/paint larger ones in the drought season, and spray during bloom. Still many seedlings every year!

Seed bank studies are a great idea for a student project!

I’m curious to know if you’ve read “The Rambunctious Garden”, and if so, what you think of the author’s thoughts on invasive plants. At first, it seemed horrendous to me, but then after reading it, I thought maybe she had a point. And…too bad about the plant thieves, maybe one of those wildlife cams could catch them in the act.

Emma Marris’ book is top of my “to read” list. Knowing some of the gist from reviews and colleagues, I think I’ll agree with her about the need to leave behind any notion of “pristine” wilderness. In this case though (Bluebell Island), we’re dealing with one of the last scraps of habitat left, so I think some measure of control of non-natives is justified under almost any philosophy. But I obviously need to read the book before having anything solid to add in way of a response.

It’s great to see an example of invasive plant removal in quantifiable terms. Local native plant groups often spearhead these types of programs, so I think it might be useful for them to see an effort that has been conducted scientifically. David, any chance this might get published one day? At the very least, it’s a prime example of the value of undergraduate research. Kudos.

After all my years in Sewanee, I have to admit that I’ve never been to Bluebell Island. Looks like it’s next on the list. I’m a real sucker for riparian forests, anyway. I’ve heard that poaching has been a concern for years; now that I’ve seen an aerial shot, I wonder if a fence and locked gate would discourage future poaching? Bluebell appears to be more of a small peninsula than an island, and one with a narrow isthmus. It’s a thought. And as a native plant gardener, I never buy a plant from a mail order source or nursery that isn’t nursery-propagated. If the nursery owner can’t answer a simple question — “What’s the source of this plant?” — or the plants appear sloppily potted, with weeds and other collateral damage (see above), that’s a tell-tale sign of a wild-gathered, poached, plant. Unfortunately, disreputable dealers create a market that encourages just this type of plundering.

A final thought: What’s the University’s position or long-term plan (if any) regarding invasive removal on the Domain? In the residential sections, at least, the invasives are distressingly common. Part of my long-term plan for my family’s yard and gardens is to eradicate (or at least greatly reduce) the invasives (bittersweet, miscanthus, honeysuckle, privet), and replace some of them with native alternatives.

William

William,

Thank you! Yes, we’ll publish at some point. The data are getting interesting now.

The island is accessible from multiple angles and via boat, so no gate would work. And a gate would keep out nature lovers would like to visit which is something the Land Trust would not want to discourage, I think.

I know of no long-term plan about invasives on the Domain. However, the Domain plan (in the works as we speak) does talk about this as a priority and there have been some small scale projects. Our goats love all exotics, so they feed well… In my opinion, bittersweet is the worst of the lot around here. It smothers trees and will tolerate shade. Birds spread the seeds. Very hard to kill.

I read this coming in from an hour outside in the cool trying to free my garden from English Ivy, periwinkle and an (ob)noxious creeping variagated mint type of plant. Ans I removed a dozen or so sprouts of English Holly and Laurel. It seems that ridding a place of invasives is much like removing marine debris … there is an endless amount and much of it seems to have its origin as non-point source. I think your data are very interesting. It would be great if it could be a 20-year study at a minimum.

BTW … Is Bluebell Island surrounded by water or is it just an area. And … are the bluebells scented?

Sue, There is something vaguely Sisyphean about the work, but it is worth doing, I think. Taking a stand and actually making a small positive difference. Maybe a large difference when connected to a class/educational mission? I hope that we can indeed continue the study for many more years.

Bluebell Island is an island in the Elk River. It is accessed across fallen logs, so the river is not that wide. But the water kept the livestock out (mostly) over the years which is why it is so floristically interesting. The flowers are unscented (despite what some websites claim). But I should double-check that in the spring.

There is an unscented bluebell that grows here in people’s gardens. It spreads rapidly, and some people say invasively, and some work to remove it. I’ll press a plant in the spring and send it to you … I wonder how it relates to your bluebell. It would be ironic if they were one and the same! (Bluebells in England are scented)

I’d be interested to see what this is. I have not heard of Virginia Bluebells being invasive in the PNW, but it is possible…

Is it perhaps this one? I have it too in Seattle http://christineinportland.com/2012/04/hyacinthoides-hispanica-spanish-bluebells-invasive-species/

replying to the post from Taylor gardens below .. yes that’s the plant. And actually I don’t really mind it .. it does not travel that fast in our patch and to my way of thinking when it comes to a flower garden there is no point in weeding out all the stuff that does not do well and replacing it with plants that struggle to survive. (Or am I making excuses to avoid weeding?)

I remember our lab to bluebell island with fondness -as I do most of them – and feel great sadness that the poaching has continued. Thank you for the reminder about asking the origin of nursery plants.

Thank you Hayden! The island is waaay better because of your work!

Pingback: Least Trillium lives on… | Ramble

Pingback: Sounds of the Valley | Clingman-Jones Family Reunion